Circuit Protection and Safety: Fuses, Circuit Breakers, and Grounding

Ensuring Electrical Safety Through Protection Devices

Author: Geetha Editorial Team

Published: Nov 11, 2025

Last Updated: Feb 13, 2026

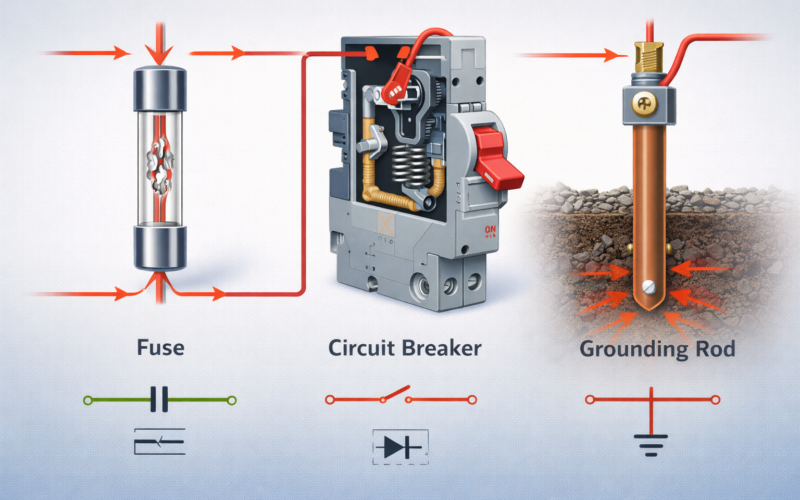

Electrical safety is paramount in any electrical system. Excessive current can generate dangerous heat, damage equipment, and cause fires. Ground faults (current leaking through people or other conductive paths to ground) present electrocution hazards. Circuit protection devices prevent these hazards. Understanding fuses, circuit breakers, and grounding systems is essential for safe electrical system design and operation.

Why Circuit Protection is Essential

Electrical hazards include:

Overload: Excessive current from too many loads on a circuit heats wires and equipment, risking fires.

Short Circuits: Accidental direct connections between high and low potential points cause current to bypass intended loads, generating extreme currents.

Ground Faults: Insulation breakdown or accidental contact routes current through unintended paths, including through people.

Arc Faults: High-resistance unintended current paths (like loose connections) create arcs that generate extreme heat and risk fires.

Circuit protection devices detect and interrupt these dangerous conditions before they cause damage or injury.

Fuses

A fuse is the simplest protection device. It consists of a metal element designed to melt when current exceeds its rating, opening the circuit and stopping current flow.

Operation: When rated current is exceeded, the fuse element heats up and melts. Melting breaks the circuit, protecting downstream equipment. Fuses must be replaced after operation.

Ratings: Fuses are rated by current (15A, 20A, 30A, etc.) and voltage. The voltage rating must exceed the circuit’s voltage to prevent arcing across the melted element.

Types:

Standard fuses open quickly at currents exceeding their rating. Used in simple circuits.

Time-delay (slow-blow) fuses tolerate temporary current surges from inrush currents (like motors starting). Useful in circuits with inductive loads.

Class designation (such as Class RK5, Class J) indicates physical size and performance characteristics. Never substitute fuses of different classes.

Advantages: Simple, inexpensive, always work (no moving parts to stick).

Disadvantages: Must be replaced after each operation, can’t distinguish between overload and short circuit, limited selectivity.

Circuit Breakers

Circuit breakers are reusable switches that automatically open when current exceeds their rating. They eliminate the need to replace components and can typically be reset by flipping a switch.

Operating Principles:

Thermal element: A bimetallic strip carrying the circuit current bends as it heats. Excessive current bends the strip enough to trigger the breaker.

Magnetic element: A solenoid around the current-carrying conductor creates a magnetic field proportional to current. Excessive current creates sufficient magnetic force to trigger the breaker immediately.

Modern breakers combine thermal and magnetic elements:

Thermal response protects against sustained overloads (slow, time-dependent).

Magnetic response protects against short circuits (fast, instantaneous).

Types and Ratings: Breakers are rated by voltage, current, and trip characteristics. Common household breakers are 15A, 20A, or 30A at 120V or 240V.

GFCI (Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter): GFCI breakers detect ground leakage currents (current flowing through unintended paths to ground) as small as 5mA. They instantly open, preventing electrocution. GFCI breakers are required for bathrooms, kitchens, and outdoor outlets.

AFCI (Arc Fault Circuit Interrupter): AFCI breakers detect high-frequency current patterns characteristic of arcing. They prevent fires caused by loose connections or damaged insulation. Required in bedrooms and living areas.

Advantages: Reusable, faster operation, better selectivity, can add ground and arc protection.

Disadvantages: More complex, more expensive than fuses, mechanical elements can fail.

Grounding and Bonding

Grounding connects electrical systems to earth, providing a safe path for current during faults. Proper grounding is essential for safety and system operation.

Equipment Grounding: Connecting metal equipment frames to ground ensures that if insulation fails, fault current flows to ground through low-resistance paths rather than through people touching the equipment.

System Grounding: Connecting the power system’s neutral conductor to ground (typically at the service entrance) establishes a reference potential and provides a return path for current.

Grounding Components:

Ground rods: Driven into earth, typically 8-10 feet deep, providing contact with soil.

Grounding buses: Collect ground connections in panels and subpanels.

Ground wires: Connect equipment frames to ground buses and service ground.

Bonding: Connecting metal objects together to maintain the same potential, preventing dangerous differences in potential.

Resistance: The effectiveness of grounding depends on earth resistance. Low resistance (typically less than 25 ohms) is desirable. Wet soil has lower resistance than dry soil; electrode depth and contact area affect resistance.

Coordination and Selectivity

In complex systems with multiple protective devices, coordination ensures that only the protection device nearest to a fault operates, leaving upstream circuits intact. This requires careful selection of breaker types, current ratings, and time-current characteristics.

Proper coordination prevents unnecessary outages and helps isolate problems. For example, if a protected sub-circuit faults, only that circuit breaker should trip, leaving other circuits powered.

Design Standards and Codes

Electrical codes (like the National Electrical Code in the US) establish requirements for circuit protection:

Breaker capacity must not exceed the ampacity of the wires it protects.

Grounding resistance must meet specified limits.

GFCI and AFCI protection required in specified locations.

Proper labeling and documentation required.

Professional designers and installers must understand and follow these codes to ensure safe systems.

Practical Considerations

When designing or modifying electrical systems:

Use breakers matched to the circuit’s requirements and wire ampacity.

Install ground rods with proper resistance testing.

Use GFCI protection in wet areas and AFCI in living spaces.

Ensure proper labeling of all breakers and circuits.

Test protective devices periodically to ensure operation.

Comparison: Fuses vs. Circuit Breakers vs. GFCI

| Feature | Fuses | Circuit Breakers | GFCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Principle | Thermal: wire melts at high current | Electromagnetic/thermal: trips bimetallic strip or solenoid | Detects ground leakage current imbalance |

| Response Time | 50-200ms (dependent on current level) | 10-100ms (adjustable) | 20-30ms (instantaneous) |

| Reusability | Single-use (must replace) | Reusable (reset after trip) | Reusable (reset after trip) |

| Cost |

Worked ExamplesExample 1: Fuse SelectionProblem: A circuit draws maximum 15A of current. Select appropriate fuse rating. Solution: Standard fuse sizes: 10A, 15A, 20A, 25A, 30A… Rule: Fuse rating ≥ maximum expected current For 15A max current, select 15A fuse (or next size up if unavailable) Why not 10A? Would nuisance-trip on normal operation Why not 20A? Would not protect against 18A fault Example 2: Ground Fault DetectionProblem: A GFCI detects 8mA leakage to ground from a wet hand. Should it trip? (Sensitivity: 5mA) Solution: Given: Leakage current = 8mA, GFCI sensitivity = 5mA Since 8mA > 5mA, GFCI will trip immediately (typically within 25ms) Safety benefit: Prevents electrocution—8mA can cause muscle paralysis Example 3: Grounding ResistanceProblem: A grounding rod has resistance 25Ω. What fault current flows at 240V? Solution: Given: V = 240V, R_ground = 25Ω Using Ohm’s Law: I = V/R = 240/25 = 9.6 amperes Interpretation: Sufficient current to trip a 15A breaker quickly, providing protection. Key Takeaways.50-2 per unit |

-30 per unit | -50 per outlet/breaker |

| Protection Type | Overcurrent only | Overcurrent (customizable) | Ground faults (to ground) |

| Typical Setting | Fixed (e.g., 15A, 20A, 30A) | Adjustable (0.5-100A+) | 5mA sensitivity (standard) |

| Best Use | Legacy systems, certain industrial | Main panel, branch circuits | Bathrooms, kitchens, outdoor |

Key Takeaways

- Fuses protect by melting when current exceeds design rating—one-time protection requiring replacement after fault.

- Circuit breakers automatically trip when overcurrent is detected—reusable protection that can be reset after fault clearing.

- Grounding provides a safe return path for fault currents—critical for shock prevention and equipment protection.

- GFCI (Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter) devices detect ground leakage currents and trip quickly—essential for bathroom and outdoor protection.

- AFCI (Arc Fault Circuit Interrupter) devices detect dangerous arcing conditions—increasingly required for fire safety.

- Overcurrent protection sizing requires balancing safety (protection during faults) with usability (avoiding nuisance trips).

- Proper grounding and bonding are essential for both safety and electromagnetic compatibility in electrical systems.

Leave a Reply