Fundamentals of Electricity: Voltage, Current, and Resistance Explained

Understanding the Basics of Electrical Systems

Author: Geetha Editorial Team

Published: Nov 11, 2025

Last Updated: Feb 13, 2026

Electricity is one of the most fundamental forces in our universe and the foundation of modern technology. From powering our homes to running complex industrial equipment, electrical systems are ubiquitous. Understanding the basic principles of electricity—voltage, current, and resistance—is essential for anyone studying electrical engineering or electronics. These three concepts form the foundation of Ohm’s Law and provide the basis for analyzing all electrical circuits.

What is Voltage?

Voltage, also known as electric potential difference, is the force that pushes electrical charge through a conductor. It’s measured in volts (V) and represents the energy difference between two points in a circuit. Think of voltage as the pressure pushing water through a pipe—higher voltage provides more “push” for the electrical charge.

Voltage can be generated through various means: chemical reactions in batteries, mechanical movement in generators, solar cells converting light to electricity, or other methods. The voltage produced by different sources varies significantly. A typical AA battery produces about 1.5 volts, household wall outlets provide around 120 volts in North America and 240 volts in Europe, while power transmission lines carry thousands of volts.

Direct current (DC) voltage is constant, while alternating current (AC) voltage oscillates between positive and negative values at regular frequencies (typically 50-60 Hz in power systems). AC is used for power transmission because it can be more easily transformed to different voltages.

Current: The Flow of Charge

Electric current is the flow of electrical charge through a conductor, measured in amperes or amps (A). One ampere represents the flow of one coulomb of charge per second. Current is like the amount of water flowing through a pipe—it tells us how much electrical charge is moving per unit time.

There are two conventions for describing current direction. Conventional current (historical convention) flows from positive to negative terminals, while electron flow is actually from negative to positive. Modern electronics engineering typically uses conventional current direction.

Current can be AC (alternating) or DC (direct). DC current flows in one direction continuously, while AC current periodically reverses direction. Different applications use different types: batteries provide DC, household power is AC, and electronic devices often use both (with AC being converted to DC internally).

The magnitude of current in different applications varies widely. A tiny electronic circuit might carry microamps (millionths of an amp), while industrial equipment draws hundreds or thousands of amps.

Resistance: Opposition to Current Flow

Resistance is the opposition to electrical current flow, measured in ohms (Ω). Every material has some resistance—perfect conductors (with zero resistance) don’t exist in practice. Resistance represents how difficult it is for charge to flow through a material.

Different materials have vastly different resistances. Copper and aluminum, excellent conductors, have very low resistance. Rubber and plastic, insulators, have extremely high resistance. Semiconductors like silicon have intermediate resistance that can be precisely controlled, making them useful for electronic devices.

Resistance depends on several factors: the material’s resistivity (intrinsic property), the length of the conductor (longer means more resistance), and the cross-sectional area (thinner means more resistance). The relationship is captured in the formula: R = ρL/A, where ρ is resistivity, L is length, and A is cross-sectional area.

Temperature affects resistance significantly. In most metals, resistance increases with temperature. Superconductors are special materials that lose all resistance below critical temperatures, though these require extreme cooling to achieve.

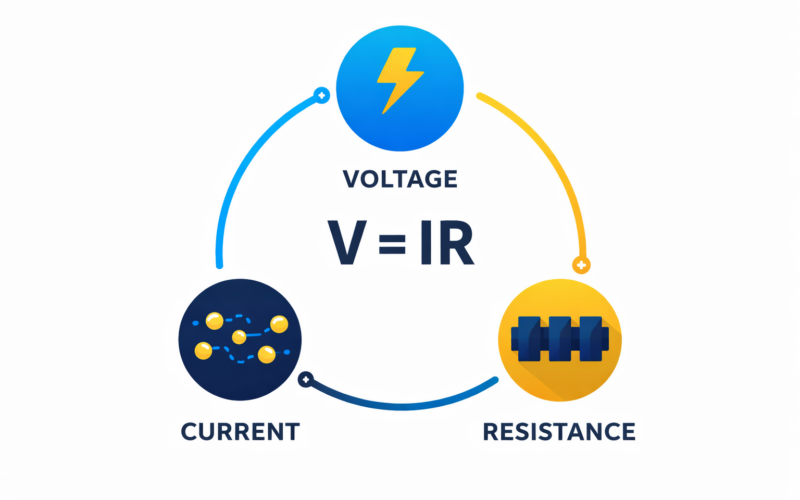

Ohm’s Law: Relating Voltage, Current, and Resistance

Ohm’s Law is the fundamental relationship governing circuits: V = IR, where V is voltage, I is current, and R is resistance. This simple relationship allows us to calculate any one quantity if we know the other two.

For example, if a resistor has 10 ohms of resistance and 2 amps of current flowing through it, the voltage drop across the resistor is 20 volts. Conversely, if we apply 12 volts across a 4-ohm resistor, 3 amps of current will flow.

Ohm’s Law forms the basis for circuit analysis and design. More complex circuits are analyzed by applying Ohm’s Law to individual components and using Kirchhoff’s voltage and current laws to solve for currents and voltages throughout the circuit.

Series and Parallel Circuits

In series circuits, components are connected one after another in a single path. The same current flows through all components. The total voltage is divided among the components proportional to their resistances. Total resistance is the sum of individual resistances: R_total = R1 + R2 + R3…

In parallel circuits, components are connected across the same two points, providing multiple paths for current. The same voltage appears across all components. Current divides among the branches inversely proportional to their resistances. The reciprocal of total resistance equals the sum of reciprocals of individual resistances: 1/R_total = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3…

Most practical circuits use combinations of series and parallel connections, optimized for specific applications. Understanding series-parallel combinations is essential for circuit design and troubleshooting.

Power in Electrical Systems

Electrical power, measured in watts (W), represents the rate at which energy is transferred. The fundamental relationship is P = VI, where power equals voltage multiplied by current. For resistive elements, we can also use P = I²R or P = V²/R.

Power dissipation in resistance generates heat. This is useful in applications like heaters and light bulbs but needs to be managed carefully to prevent overheating in electronic devices. Proper heat dissipation (often using heat sinks and fans) is critical in high-power applications.

Practical Applications

Understanding these fundamentals enables analysis and design of practical systems. In power distribution, engineers manage voltage and current to minimize losses. In electronics, proper resistor selection ensures circuits operate at designed specifications. In safety, understanding current limits helps prevent electrical hazards.

The principles of voltage, current, and resistance extend to more complex analyses including AC circuit analysis (adding reactance and impedance), transient analysis (studying circuit behavior when switched), and frequency response (analyzing circuit behavior at different frequencies).

Worked Examples

Example 1: Calculating Voltage using Ohm’s Law

Problem: A resistor of 10Ω carries a current of 2.5A. Calculate the voltage drop across the resistor.

Solution:

Given: R = 10Ω, I = 2.5A

Using Ohm’s Law: V = IR

V = 2.5 × 10 = 25 volts

Verification: A 10Ω resistor with 2.5A current creates 25V drop, which is reasonable for household circuits.

Example 2: Series Circuit Current

Problem: Three resistors (5Ω, 10Ω, 15Ω) are connected in series with a 60V power source. Calculate the current flowing through the circuit.

Solution:

Given: R₁ = 5Ω, R₂ = 10Ω, R₃ = 15Ω, V = 60V

In series: R_total = R₁ + R₂ + R₃ = 5 + 10 + 15 = 30Ω

Using Ohm’s Law: I = V/R = 60/30 = 2 amperes

Voltage drops: V₁ = 2×5 = 10V, V₂ = 2×10 = 20V, V₃ = 2×15 = 30V (sum = 60V ✓)

Example 3: Power Calculation

Problem: A heating element draws 5A of current at 120V. Calculate its power consumption.

Solution:

Given: I = 5A, V = 120V

Using Power formula: P = VI

P = 120 × 5 = 600 watts

Interpretation: The heating element consumes 600W or 0.6 kW of electrical power.

Key Takeaways

- Voltage is the electrical force that drives charge through circuits, measured in volts—think of it as the “push” making electricity flow.

- Current is the actual flow of electrical charge, measured in amperes—representing how much charge moves per unit time.

- Resistance opposes current flow (measured in ohms) and depends on material properties, length, and thickness of the conductor.

- Ohm’s Law (V = IR) connects all three concepts—knowing any two lets you calculate the third, essential for circuit analysis.

- Series vs. Parallel circuits distribute voltage and current differently—series current is constant, parallel voltage is constant.

- Power (P = VI) measures energy delivery rate—understanding how voltage and current combine helps predict energy consumption.

- Master these fundamentals to understand everything from simple circuits to complex power systems and electronic devices.

Leave a Reply